Unlock the Editor’s Digest for free

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

The Australian politician Julia Gillard once wondered what it was about “the air in England that makes conservatives care about climate change”. The Conservative party’s commitment to a greener planet made it an outlier among parties of the centre-right for a long time. And their contribution has gone well beyond caring: the actions of Tory governments, whether Margaret Thatcher weaning the UK off coal, the development of nuclear power stations under Thatcher and John Major or the embrace of renewables under David Cameron, made a significant contribution to the UK’s reduced emissions.

But now something has changed. The British Conservatives are no longer an exception as far as climate is concerned. First Rishi Sunak, and now Kemi Badenoch, have watered down the party’s climate commitments under the guise of “realism”. Badenoch now argues that the UK’s target of reaching net zero by 2050 cannot be met “without a serious drop in our living standards or by bankrupting us”.

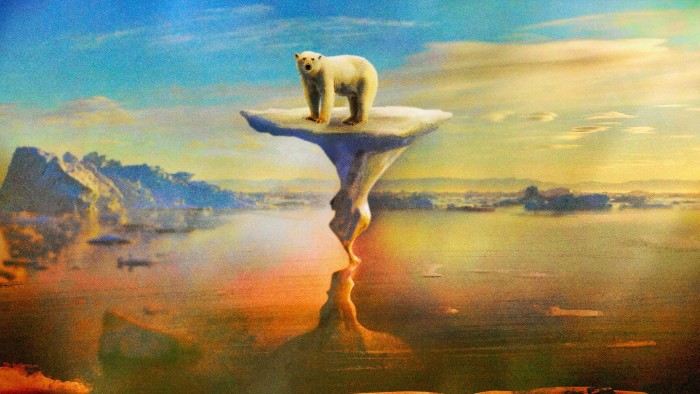

Given the UK’s size, the country’s own contribution to net zero was always going to be important largely as a demonstration of how you can manage the green transition while still being electorally successful, rather than being a significant contributor to the global fight against climate change in its own right. It matters not so much because of its direct impact, but because it symbolises how even once-reliable fighters for reduced emissions are becoming at best false friends.

How did this happen? It was not so long ago that Boris Johnson made net zero a central plank of his 2019 manifesto, or that David Cameron saw environmentalism as a way of demonstrating that his party had changed and as a reassuring link back to its Thatcherite past.

Part of the story is that their successors have overestimated the political power of climate retreat. To the extent that Rishi Sunak’s muddled re-election campaign had any messages, one was that he was a redoubt against climate “zealots”. The result was a disaster. In British politics, having something serious to say about climate change is a “hygiene factor” for most voters: it’s a sign that you are grounded in the real world and are across the major problems facing the UK.

One reason for the shift is that the green transition is now seen as a way to smuggle leftwing ideas in by the back door — Gareth Davies, the Conservative MP for Grantham and Bourne, warned a few years ago that treating climate change as “a Christmas tree” on which to hang all sorts of leftwing nice-to-haves had made it less attractive for some on the right. Another reason is that, rightly or wrongly, the party sees it as a way to neutralise the Reform UK threat.

But the Conservative retreat from net zero is about something more fundamental than leftist over-reach or fear of a rightward challenge. It is about a party doing what first-term oppositions so often do — retreating from seriousness. There is, it’s true, a case to be made that given Donald Trump’s victory in the US and the collapse of functioning organisations where countries can co-operate globally, the chances of reaching net zero are now so slim as to be meaningless. It is just not the case that Badenoch is making. Instead of the two choices facing the UK — spending money to reach net zero or spending rather more money to try to survive in a chaotic world where net zero is abandoned — she proposes the UK do neither.

What’s striking about Badenoch’s change of approach is that she appears to envision that it’s not just that the UK will delay or abandon its aims to change the climate, but that the climate will delay or abandon changing the UK. She proposes no new spending or alterations to how we live our lives or how to rebuild or retrofit the country’s Victorian infrastructure to weather greater extremes of climate.

Her “realistic” approach to net zero is, in practice, that both politicians and the planet agree to put all this unpleasantness behind them. Just as the Labour government refuses to accept that Donald Trump’s presidency means its previous plan of tight spending for everything but the NHS until re-election no longer holds, the opposition under Badenoch desperately wants a national project more suited to Conservative pieties than net zero.

The tragedy for both government and opposition is that these real world challenges have to be faced — they can’t be wished away. The air in England might no longer nurture Conservatives who care about climate change, but the need to prepare for and seek to avoid as much of the damage of a changed climate as possible hasn’t gone away, no matter how much Badenoch might wish it has.