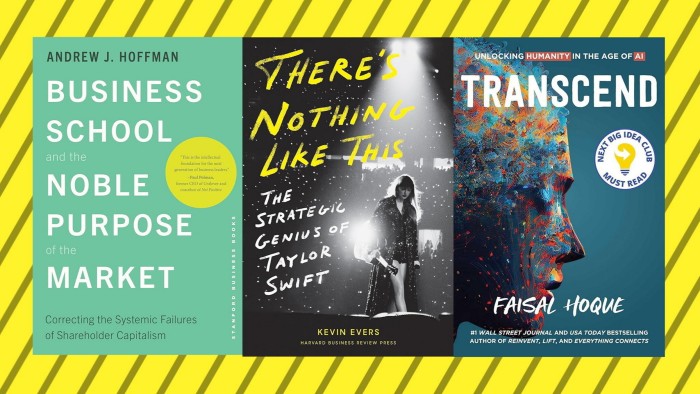

“Business school and the noble purpose of the market: Correcting the systemic failures of shareholder capitalism”, by Andrew Hoffman

Is capitalism working — and if not, can business schools help fix it?

Andrew J Hoffman, a professor of sustainable enterprise, argues that business education is overdue for reinvention. In this timely book, he contends that MBA programmes are still anchored in an outdated model of shareholder primacy, despite growing evidence this ideology has contributed to inequality, ecological collapse and political distrust.

True to this premise, the author argues for substantive change. Business schools, he says, must go beyond adding electives in sustainability and ethics. They must rebuild their curricula, pedagogies and incentives from the ground up, fostering leaders who act not as profit-maximising agents but stewards of the market.

The book’s strength lies in its true-to-life portrayal of academia, acknowledging the challenges of institutional inertia, faculty reward structures and student disillusionment. Despite these obstacles, Hoffman can draw on plenty of experiments and work for change within the academic system. He encourages students to take an active role in shaping their own educational experiences.

Some may find the book idealistic. But Hoffman’s urgency is grounded in common sense. Change will be difficult, he admits, but he believes it is possible, perhaps led by schools willing to rethink the MBA entirely.

This is a wide-ranging, thoughtful guide that connects history, law, economics and education. Its aim is not to tear capitalism down, but to rebuild it from its foundations. Whether business schools are willing to lead or be left behind remains an open question. Leo Cremonezi

“Transcend: Unlocking humanity in the age of AI”, by Faisal Hoque

Artificial intelligence — and particularly generative AI — is such an all-pervading technology, and so fast moving, that it seems likely to generate endless demand for books about how to use it well and safely. Faisal Hoque’s contribution to this growing pile is a strange hybrid. He frames the challenge as a philosophical and practical exploration of humanity and human potential.

Most busy business readers, alas, are likely to skip the philosophy and dive into the practical guidance that takes up most of his book. Hoque is a lover of acronyms. He applies two of them to individuals, businesses, and government. His first is “open”, for unlocking AI’s potential — outline, partner, experiment, navigate. His second is “care”, for mitigating its dangers — catastrophise, assess, regulate and exit. Fictional case studies are used to illustrate the framework: a new chief executive of Nike considers the risks and rewards of launching AI-driven products for disabled athletes; an innovation official at a US government agency looks at the benefits and disadvantages of a new AI investment-matching platform.

These are useful exercises, but they sit a little awkwardly next to Hoque’s loftier examination of humanity. “If AI is a kind of philosopher’s stone, can it offer spiritual riches as well as material benefits?” he asks in the final part of the book, which takes up the title theme. Citing St Augustine, he concludes that the right attitude to AI is “a loving one”. Call me a cynic, but I don’t see that going down well with Nike’s directors or Donald Trump’s cabinet members. Andrew Hill

“There’s nothing like this: The strategic genius of Taylor Swift”, by Kevin Evers

Kevin Evers, an editor at Harvard Business Review, believes that Taylor Swift’s business strategy should receive the same critical attention as that of Steve Jobs, Elon Musk, or Jeff Bezos.

There’s nothing like this is a biography not just of the songwriter, but also the savvy strategist, whose ability to not just withstand but grow from pressure Evers defines as “antifragile”. Evers’ book traces its subject’s ascent to superstardom with enough clarity for a casual audience and enough detail to engage even the most obsessive fans (I include myself in the latter group).

While some of its comparisons feel a little stretched — Taylor Swift is not an iPhone — Evers’ biography is an engaging exploration of how her business acumen has shaped her artistry, and vice versa. There are also refreshingly few references to the personal romantic connections that have long dominated coverage of the singer.

The album-by-album account of the songwriter’s constant reinvention doubles as a tale of the sweeping changes that have shaken the music industry in the digital age. According to Evers, Swift has not just successfully adapted, but personally shaped the business model for an internet-age artist, from pioneering digital engagement with fans on MySpace in the early 2000s to grappling with the rise of music streaming and the dawn of TikTok.

It’s a sharp and comprehensive analysis, although some of the metaphors might be a little confusing if you’re not acquainted with the songwriter’s lyrics. Prepare for plenty of references to old cardigans and red scarves. Stephanie Stacey

‘Shatterproof: How to thrive in a world of constant chaos (and why resilience isn’t enough),’ by Tasha Eurich

When life gives you lemons, make lemon cheesecake.

That’s the core premise of organisational psychologist Tasha Eurich’s prescient research into stress and success. The book challenges traditional concepts of weathering adversity, arguing that “bouncing back” is not a viable strategy for meeting the demands of the modern world. Rather than helping us float, trying to stay above water is causing us to drown. The solution, Eurich says, is to find a way to harness challenges and use them as opportunities for personal development.

Shatterproof provides a step-by-step approach to that transformation, broken down into broad categories of reflection, research, and revision. Eurich presents the idea that resilience is not just a myth but three myths stacked in an ill-fitting trenchcoat. Old biology, she argues, is ill-equipped to deal with new-aged adversity and instead of pushing through pain, we need to recognise and address it, beginning with the realisation that many of us aren’t coping as well as we think.

The author then suggests practical steps for constructively confronting emotional dysregulation, outlining the underlying psychological needs that drive stress responses and the mindset shifts needed for growth. In its final section, Shatterproof becomes a workbook, guiding readers through three key shifts needed to respond to stress with intention rather than grit: restoring self-worth, embracing a value-driven mindset and building strong relationships.

In many ways, Shatterproof is not designed to be read so much as used, and its strength lies in its clarity and purpose rather than its prose. As a structured workbook and a distillation of thoughtful research, it offers a practical, grounded approach to tackling stress and emotional strain that many will find strikingly relevant in the current climate. Cordu Krubally-N’Diaye