Unlock the Editor’s Digest for free

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

The writer is John Snow Professor of Epidemiology and director of the Center for Infection and Immunity at the Columbia University Mailman School of Public Health

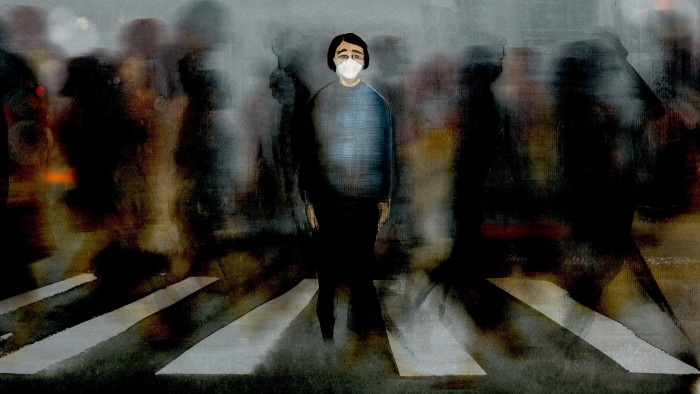

Would you step off the kerb at a busy intersection without scanning for traffic? Of course not. Yet we do the equivalent every day by neglecting infectious disease surveillance.

Our collective awareness of emerging infectious diseases began decades ago with HIV/Aids, Ebola and West Nile virus. These diseases — along with Sars, Mers, Zika, mpox and novel influenzas — originated in animals before jumping to humans. More will follow.

But zoonotic spillovers aren’t the only threat. The number of high-containment labs handling dangerous pathogens has exploded. In the 1980s, fewer than 10 studied lethal threats such as Ebola and Marburg for which there are no effective drugs. Today, there are at least 69. There is no formal registration of the type of lab used to study potentially lethal airborne viruses like Sars and Sars-Cov-2. However, estimates range into the thousands with 1,300 in the US alone.

While this research is vital, it carries risks. From 2000 to 2021, there were 309 reported lab-acquired infections worldwide, resulting in eight fatalities. Even worse, some nations are now weaponising pathogens. Russia has reportedly reactivated Sergiev Posad-6, a Soviet-era bioweapons facility near Moscow. North Korea’s programme is also active. Non-state actors pose risks, too. Viruses can be built from scratch using sequences in public databases. And while the companies that synthesise viral genes do monitor requests, anyone can buy used, earlier-generation equipment online and produce whatever they want with no oversight at all.

We live in a world where new threats can arise through exposure to infected animals, lab accidents or deliberate efforts by terrorists or rogue states. And it’s not just the exotic infections that should worry us. Antibiotic resistance can derail recovery from a routine hip or knee operation. The introduction of a virus like H5N1 (avian influenza) can also wreak economic havoc.

We may not be able to control wild animal markets, rogue laboratories or the overuse of antibiotics. But we can and must stop flying blind.

The term surveillance comes from the French sur (over) and veiller (stay awake), derived from the Latin vigilare, also the root of the term vigilance. The term surveillance implies active, continuous, comprehensive vigilance to spot potential threats. Yet no national or international organisation has the mandate or resources to perform this function.

Furthermore, what limited capacity for surveillance we did have is rapidly disappearing given the withdrawal of financial and political support for organisations like the World Health Organization and health ministries worldwide.

Surveillance is currently mostly passive. The general population relies on health departments to voluntarily provide information. This can only be as accurate as the effort that governments put into getting that information and how transparent they are in sharing it. We need more active surveillance systems that can identify infectious threats.

I was an early developer of diagnostic tools for detection of infectious agents. Over the past 40 years, I’ve seen the tools become more sensitive and less expensive. It is now feasible to build portable equipment that takes samples from air or wastewater, then extracts and sequences the genetic material, flagging known or novel pathogens, either natural or engineered.

Such equipment could be placed at ports of entry for tourists and trade and used to continuously screen for infectious threats to public health or agriculture. It could be specifically deployed wherever there is a burst of activity consistent with the appearance of a new infectious disease. With approval from regulatory agencies, it could also be used in clinics and hospitals to enable accurate diagnosis of infectious diseases, better clinical outcomes and reduced costs.

But surveillance cannot stop at national borders. The best defence is spotting outbreaks at their source. The most straightforward way to do this is to train and equip local scientists in high risk areas with sequencing tools — near wildlife, high level biocontainment facilities, population centres or cites of mass gatherings. Such support should be linked to data transparency.

Pandemic fatigue is real, but complacency is deadly. The next threat could emerge anywhere, anytime. Investing in smart, scalable surveillance isn’t alarmism — it’s pragmatism.