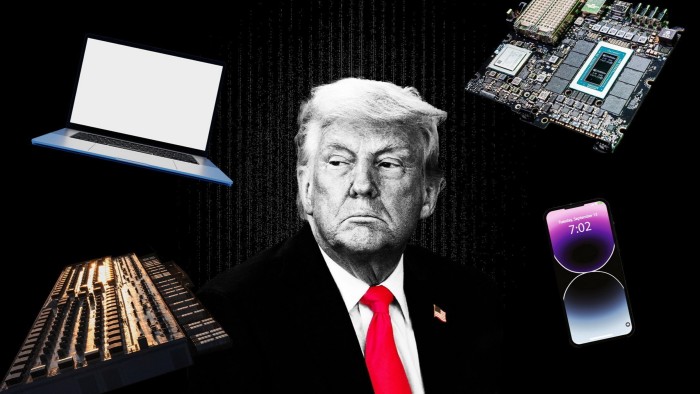

Donald Trump’s global tariff regime is endangering his ambitions of encouraging domestic chip production while hampering US goals of dominating the race to develop world-beating artificial intelligence.

Industry insiders, including tech executives, supply chain experts and analysts, said the US president’s escalating trade war is likely to hinder the expansion of American computing power. This is because the measures may drive up costs for building semiconductor fabrication plants and AI data centres in the US.

The tech sector’s concern is that the effort to force greater onshoring of the chip and electronics manufacturing will have the unintended effect of holding back the likes of OpenAI, Google and Microsoft which are seeking to beat counterparts in China in building advanced AI.

“The economic uncertainty induced by Trump tariffs could become the single largest barrier to American AI supremacy,” said Sravan Kundojjala of consultancy SemiAnalysis.

Big Tech groups, including Microsoft, Google, Amazon and Meta have pledged to spend $300bn on the computing infrastructure that underpins AI in 2025 alone.

Other projects, such as a $100bn commitment by Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company to boost chipmaking capacity in the US, will help to support such ambitions

Industry figures warned these efforts face uncertainty and disruption as tariffs hit the complex global supply chains that serve large AI computing projects.

“I am much more worried about the impact on a single component in a given data centre that may be delayed now because some [overseas] supplier is making a decision about their business,” said a person involved in the development of Stargate, the US $500bn data centre project being led by OpenAI, SoftBank and Oracle.

“These are fairly complex builds [which can be] delayed because of a switch for the fans.”

Semiconductors and related chipmaking equipment, materials and components were exempted from the US president’s now paused “reciprocal” tariffs announced against dozens of US trading partners.

But analysts said that the tariff regime that remains, including the 145 per cent duties on goods from China, would still push up the cost of construction and financing for fabrication plants and AI data centres in the US.

Altana, a research group which maps global supply chains said the China tariffs alone mean American data centre developers face an increase in annual costs of more than $11bn.

The US announced this week it is investigating the national security implications of importing semiconductors and swaths of related chipmaking equipment, materials and components, as it seeks to force companies to shift production of advanced AI-related hardware to the US.

The probe, known as a Section 232 investigation which could take up to 270 days to complete, could result in even more onerous demands on the industry. Trump has already invoked Section 232 powers to impose 25 per cent tariffs on the steel, aluminium and auto sectors.

“NOBODY is getting ‘off the hook’”, Trump wrote in a social media post on Sunday, adding his administration will be “taking a look at Semiconductors and the WHOLE ELECTRONICS SUPPLY CHAIN.”

However, analysts said imposing new duties on semiconductor imports would prove difficult because most chips enter the US as components already integrated into other products such as smartphones, laptops or the graphics processing units used in AI data centres.

That includes Nvidia’s most advanced GPUs, which are used by cloud service providers such as Amazon and Microsoft to train and operate the large language models of companies including OpenAI, Google and Elon Musk’s Grok.

Mohammad Ahmad, chief executive of supply chain data analysis platform Z2Data, said that most AI GPUs enter the US in the form of servers or racks of servers, which themselves are assembled in a multi-step process involving several different countries.

The GPUs contain chips produced predominantly in Taiwan or South Korea but often sent on for packaging and testing in south-east Asian countries like Malaysia and the Philippines.

The chips are then sent either back to Taiwan or to Mexico for printed circuit board assembly, where new components are added before integration into the servers exported to the US for use in AI data centres.

“Even if the GPU itself is exempt from tariffs, you are still going to get hit by massive costs in the US if tariffs still apply to the components,” said Ahmad. “The number of product categories is so vast, and the smallest component can bring your supply chain down.”

SemiAnalysis’ Kundojjala noted that even with the 32 per cent tariff proposed by the Trump administration for imports from chip manufacturing leader Taiwan, semiconductor production in the US would still be more expensive because the tariffs push up prices for key tools and materials.

“The threat of the US kneecapping itself in the ability to rebuild onshore manufacturing is real,” he said. “It will be cheaper to build manufacturing capacity outside the US, while companies with the highest share of US manufacturing stand to lose the most.”

An executive at a Taiwanese chip design house that supplies Amazon said that if hefty tariffs are imposed on the sector, his company’s US customers would have to absorb the costs for years to come.

“Amazon’s first reaction is to go to their supplier and say, ‘you guys produce this in Taiwan, and that creates extra cost for me, so reduce your prices,’” they said.

“[Amazon is] not going to demand that we have the chip made in the US because it will take years to build the capacity and build the product,” the person added. “But we will not lower our prices — if we do, we’ll be screwed by the US government because we would be frustrating their policy of forcing people to make all chips in America.”

Geoffrey Gertz, a senior fellow at the Center for a New American Security in Washington, said that the Trump administration still had the capacity to address the risks to its AI industry following the section 232 investigation with “a much broader potential toolkit using government procurement policies, changes to tax laws, and other trade or non-trade policies to adjust the national security risk arising from these imports.”

He added: “The question is whether this process ends quickly with a 25 per cent tariff on chips, or whether this will be a more creative policy process that considers a broader range of potential outcomes.”

Additional reporting by Melissa Heikkilä in London