Rising temperatures will drive the global spread of a killer fungus that infects millions of people a year, according to new research on how climate change is stoking severe disease threats.

The Aspergillus family could expand its reach to more northerly swaths of Europe, Asia and the Americas, underscoring the stealthy menace of moulds already estimated to be a factor in 5 per cent of all worldwide deaths.

Climatic shifts are broadening the geographical reach of many potentially lethal pathogens, such as those borne by mosquitoes. Fungi are a particular peril, due to their hard-to-detect spores, a shortage of treatments for the diseases they trigger, and growing resistance to existing drugs.

The world is now approaching a “tipping point” in the proliferation of fungal pathogens whose habitats range from arid earth to warm damp corners of houses, warned Norman van Rhijn, co-author of the new Aspergillus research.

“We’re talking about hundreds of thousands of lives, and continental shifts in species distributions,” said van Rhijn, a Wellcome Trust research fellow at Manchester university who specialises in fungal infections and microbial evolution. “In 50 years, where things grow and what you get infected by is going to be completely different.”

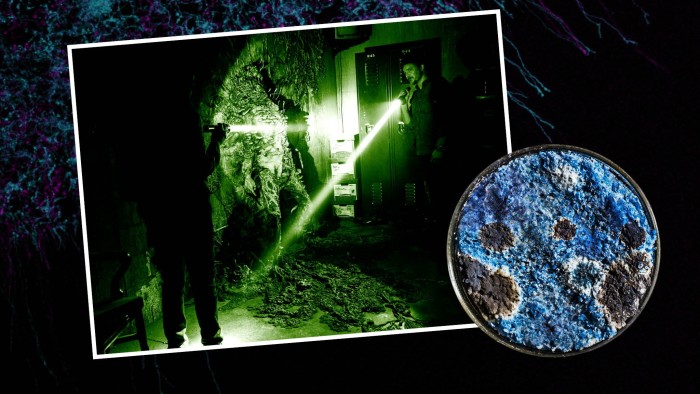

The fictional brain-altering fungus portrayed in the post-apocalyptic television series The Last of Us as wiping out much of humanity brought the threat to a wider audience. But the danger in the real world is still under-appreciated.

Mycology, the study of fungi, is a field of many mysteries. More than 90 per cent of fungal species “remain unknown to science”, according to a 2023 report by the UK’s Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew. That makes them much less well understood than big parts of the plant and animal kingdoms.

About 3.8mn people each year die with invasive fungal infections, with the pathogen being the main cause of death in 2.5mn of those cases, according to research published last year.

A leading danger is aspergillosis, a lung disease caused by aspergillus spores that can spread to other organs including the brain. Many infections are spotted late or never, because of medical practitioners’ unfamiliarity or because symptoms are mistaken for those of other conditions.

Aspergillus, named in the 18th century for its resemblance to a device used to sprinkle holy water, has brought humanity benefits as well as jeopardy.

Some species have uses ranging from industrial chemistry to the fermentation of soy sauce and sake, but others are potentially hazardous to health.

While most people don’t get sick from inhaling aspergillus spores, the mortality rate can be high if infection takes root. They are a particular threat to the growing numbers of people with immune systems weakened by conditions such as asthma or cystic fibrosis, or through medical treatments such as chemotherapy.

The species Aspergillus fumigatus was named as one of four critical fungal pathogens that posed the highest risk, according to the first ever such list of threats published by the World Health Organization in 2022.

The latest fungal research, funded by Wellcome and released on Saturday, said that A. fumigatus could spread to an additional 77 per cent of territory by 2100 if the world continues to use fossil fuels heavily. Its range would push towards the North Pole, exposing an extra 9mn people in Europe to infection.

The species can grow “astonishingly quickly” at high temperatures in compost where it lives, said Professor Elaine Bignell, co-director at the MRC Centre for Medical Mycology at Exeter university.

That could have equipped it to survive and thrive in the human body’s temperatures of around 37C. “Its lifestyle in the natural environment may have provided A. fumigatus with the fitness advantage needed to colonise human lungs,” Bignell said.

A second species in the latest study, Aspergillus flavus, lives on many crops and could spread into an additional 16 per cent of territory by 2100, the researchers project.

This would give it new or bigger footholds in north China, Russia, Scandinavia and Alaska, while making some existing habitats in African countries and Brazil inhospitable. That disappearance would have mixed effects, since it would disrupt ecosystems in which aspergillus plays a vital role recycling chemicals crucial to life.

The prospect of A. flavus geographical spread was “potentially very worrying”, said Darius Armstrong-James, professor of infectious diseases and medical mycology at Imperial College London. Research has suggested the species has caused disease outbreaks in countries such as Denmark, he added.

A. flavus also produces damaging chemicals called aflatoxins that can cause cancers or life-threatening liver damage. Higher temperatures and CO₂ levels can boost the toxin’s production and contaminate its crop hosts, scientists have found.

“There are serious threats from this organism both in terms of human health and food security,” Armstrong-James said, adding that recent data suggested A. flavus may develop high resistance to fungicides.

The development of anti-fungal medicines has been hobbled by the financial unattractiveness of investing in them, because of high costs and doubts over their profitability.

The new Aspergillus research adds to a growing body of work that suggests extreme weather events and related phenomena such as wildfires are likely to boost the spread of dangerous fungi.

Droughts followed by heavy rain may trigger soil disturbance and spore release into the air, said Brittany Bustamante, a University of California, Berkeley scientist studying the epidemiology of aspergillosis.

UC Berkeley is leading a five-year project to use big data to analyse medical records from 100mn patients in the US, to identify factors that affect the incidence and severity of fungal infections.

The researchers have found that fungal pathogens such as Coccidioides, the cause of the potentially severe respiratory disease Valley fever, spread more widely after drought and other climate-linked changes.

Coccidioides, which lives in the soils of hot and dry regions, has already expanded its habitat from the south-western US into Washington state.

Since 2020, data suggested the biggest increases in aspergillosis had been in Latino individuals and people who lived in rural areas, Bustamente said.

The reasons for this were not clear, but could be linked to people who’d had severe Covid — and perhaps were unable to access treatment from overwhelmed health systems.

“Given the potential for climate change to drive future respiratory illness surges, secondary fungal infections like aspergillosis are likely to remain a serious public health concern,” Bustamente said. “And the people most at risk will likely be those already facing structural disadvantages and greater exposure to environmental risks like pollution.”