Stay informed with free updates

Simply sign up to the US companies myFT Digest — delivered directly to your inbox.

The writer is a longtime Silicon Valley investor

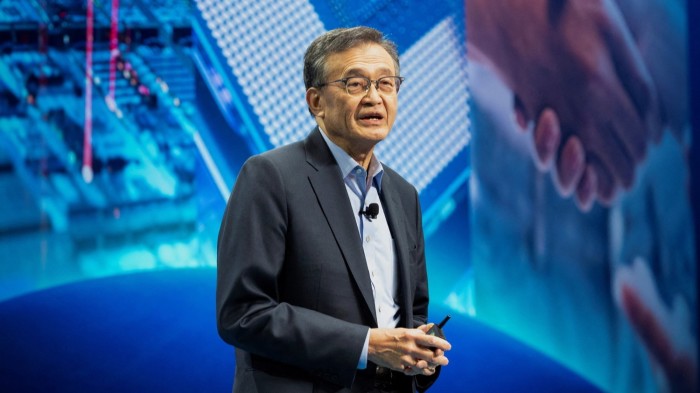

The latest character that US President Donald Trump is attempting to assassinate is Lip-Bu Tan, recently appointed chief executive of Intel. Firing from his perch on Truth Social, the president wrote, “The CEO of INTEL is highly CONFLICTED and must resign, immediately.”

While presidents have sometimes expressed their outrage about the behaviour of a corporate sector, Trump’s assault has no modern precedent.

The source of the president’s ire (and that of Tom Cotton, Republican chair of the Senate intelligence committee), is Tan’s business dealings with China as both venture capitalist and in his prior role as CEO of California-based Cadence Design Systems, a maker of electronic design systems.

The president and senator point to a $140.6mn payment agreed by Cadence last month as part of a plea agreement to settle claims of illegal exports to China between 2015-2021. They have also lambasted Tan’s venture investments in a number of Chinese semiconductor companies. In addition, they are seeking to question whether, with Tan at the helm, Intel is jeopardising the $8bn grant it was given under the Chips and Science Act that was passed by the Biden administration. The attack on Tan comes at a time when the president’s policy towards China — and the Chinese tech sector — seems to change by the hour.

Of course, it’s much easier to smear a man with accusations than examine his record and character.

Tan, 65, is a longtime American citizen and much-admired figure in Silicon Valley who is known for operating with a soft-spoken, authoritative dignity. I have known him as an acquaintance for almost 40 years and can think of no one better equipped to transform Intel’s fortunes.

Born in Malaysia and educated in Singapore, Tan studied at MIT, where he was awarded a master’s degree in nuclear engineering. After moving to San Francisco he joined the Walden Group, one of California’s early venture firms.

Instead of ploughing the Silicon Valley furrow, he elected to head to Taiwan. Later, he made investments in China — the majority in companies with deep technology roots. His deep understanding of both Taiwan and China is an asset many US CEOs would like to possess.

When he later became CEO of Cadence, which had fallen on hard times, the wiseacres assumed he would fail given his lack of operating experience. Instead, he transformed the business. In his 12 years at the helm the company’s revenue tripled to almost $3bn and the stock price appreciated by over 3,200 per cent. Today, Cadence is worth close to $100bn.

Earlier this year he became the CEO of Intel, a job which in my book amounts to public service. It is no secret that over the past 20 years Intel has ceded its mantle as the world’s most important semiconductor company to companies such as Nvidia, Broadcom, TSMC and Samsung.

Six different leaders have failed to return Intel to the glory days that it enjoyed under the late Andy Grove. It failed to capitalise on the rise of the mobile phone industry and was outgunned by Nvidia as the supplier of silicon engines for the AI revolution. Its manufacturing prowess — a rarity among US chip companies — has been consigned to the shade by TSMC. Today, Intel is an also-ran, lacking much in the way of financial firepower.

The last thing Tan needs is to be distracted by a vindictive political sideshow. Now the Intel board must decide whether to march to the beat of so many other corporate leaders and capitulate to the president’s artless bullying or to set an example for other companies and display some backbone. Early signs of defiance are encouraging. Let’s hope that Intel’s overseers abide by the refrain of that old Tammy Wynette song and continue to “stand by their man.”