Unlock the Editor’s Digest for free

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

Defence is the new tech when it comes to hot sectors. Or is it the other way round? That’s a question worth asking as defence stocks have rallied in recent weeks on everything from news of Donald Trump’s “Golden Dome” missile defence shield, to the new UK-EU security pact that would give UK defence companies access to Europe’s €150bn defence fund, to the broad understanding that US-China strategic competition is here to stay and Europe will be spending more on its own defence.

The issue is whether all this new spending will pay off, or whether technology disruption is changing not only the nature of war but the business of defence itself.

Military budgets in the US have long been huge (defence is the single largest item in the federal budget) and are getting even bigger under Trump. The president has requested a record $1tn for defence in the “big beautiful” budget bill, which just passed the House by one vote and will now go to the Senate.

Chinese military spending is also on the rise: the country is the second-largest spender after the US and has the world’s largest navy. Europe’s defence investment is set to increase sharply too, as it reprioritises its own security in the wake of Russia’s war in Ukraine and as the sense grows that the US has become an unreliable ally.

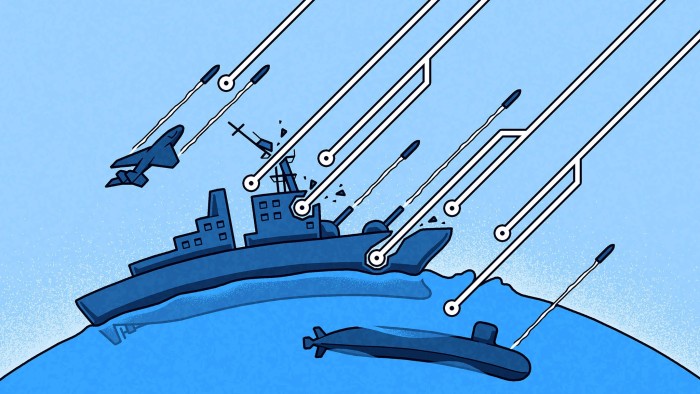

But much of this new investment is going to legacy items, such as F-35 fighter jets, ships and submarines. Trump’s missile defence plans are straight out of the Reagan-era Star Wars playbook. Some analysts have begun asking whether — even considering increased global conflict — this is money well spent at a time when technology is shifting the nature of war.

Cheap drones and missiles can, after all, now take out lines of Russian tanks moving into Ukraine. They have also been used by Houthi rebels in the Red Sea to destroy multiple ships and force the US into spending almost a billion dollars on military operations.

In some ways, Ukraine has been a testing ground for this shift in warfare. As Erik Prince, founder of the private military company Blackwater who now heads private equity firm Frontier Resource Group, noted in a February speech on the future of war, the Russia-Ukraine conflict has “massively accelerated warfare” in a way that we haven’t seen “since Genghis Khan put stirrups on horses”.

Today, innovations such as 3D-printed canister explosives on drones guided by software can take out Russian tanks for a few thousand dollars, while hackers figured out how to jam the navigation systems of American-made $150,000 javelin missiles within weeks. Add the growing power of artificial intelligence and you have, says Prince, who is a former Navy Seal, a situation in which the next big military innovations probably won’t come from the Pentagon, or even the defence research and development agency Darpa, but from “smart people” in “their garages”. As he put it, “trillions of dollars of installed capacity” is becoming obsolete.

This “tech-driven deflation and decentralisation have come in a major way to warfare for the first time”, according to market analyst Luke Gromen, who has also covered the topic recently. He likens the defence industry’s problem to an “incumbent’s curse” similar to Netflix’s decimation of Blockbuster Video, in which old-line defence firms will be outpaced by ground-up innovation. Louis Gave of Gavekal Research has called it “the Microsoft-ification of warfare”, a trend that could “undermine the comparative advantage of the world’s military superpowers”.

Just as companies such as IBM and Microsoft democratised PC ownership (you used to have to work for a large company to get access to mainframes), so ground-up innovation is shifting the nature of warfare today. This has potentially profound implications for incumbent defence contractors from Raytheon to BAE Systems to GE Aerospace and others who have seen their share prices rise in the recent market rallies. Their products could end up being the military equivalent of a mainframe computer compared with the laptops increasingly used on the battlefield.

Of course, these companies have their own innovation efforts under way. There are also many cutting-edge start-ups from Silicon Valley to Israel that aim to capitalise on high-tech, decentralised warfare. But the changing nature of war is not just a market question — it has macroeconomic and geopolitical implications as well. As Gromen puts it: “Western investors are operating based on a first principle of US military dominance as an infallible fallback support for US foreign policy, economic policy, and the USD system itself.” What if that assumption is incorrect?

For starters, you would be likely to see decreased reliance on the US manufacturers — something that is already happening, as evidenced by Europe’s rearmament plans, which rely on EU firms. It also begs the question of whether the US can afford to boost military spending at a time when debt and deficit levels are raising alarms. Finally, the democratisation of warfare gives both individuals and individual nations more defence autonomy. Success in this new world may be measured less on budget size and more on tech savvy.